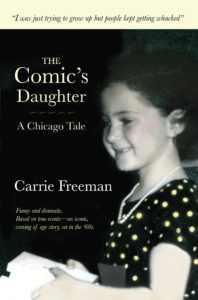

LOG LINE

Based on a true-crime, coming-of-age memoir, The Comic’s Daughter: A Chicago

Tale begins in 1963. When the teenaged daughter of a talented, philandering

nightclub comic testifies at a Mafia murder trial, it launches her dramatic and

sometimes funny struggle to break free from the vice grip of her father’s suffocating

narcissism, her mother’s icy rejection, and dark secrets that threaten to annihilate

the family.

SYNOPSIS

The Comic’s Daughter centers on the conflicted and enmeshed relationship

between 13-year-old protagonist CATHY and her father DINK, THE COMIC, the

story’s charismatic antagonist.

CHICAGO, 1963: Cathy jumps into the front seat of her family’s Datsun, ready to cut

7th-grade volleyball. “Hi, Mom.” HELEN, The Comic’s Wife, stares straight ahead and

delivers the following with her cool, deadpan panache: “Plans have changed. We’re

not going to the dentist. Joni shot Johnny, and he’s dead.” This event informs the

next seven years of her life. Cathy is – was, their constant babysitter and the last

person to see Johnny alive.

(JOHNNY MANCUZZO is The Comic’s new agent. His wife JONI is a beautiful blonde

singer. When Cathy and her mother are subpoenaed to testify for the defense at The

People vs. Joni Jaden Mancuzzo trial, the FBI is unexpectedly stationed at their house

day and night. Because Johnny’s father is the “John Gotti” of Chicago, the Mafia

wants Joni and all witnesses in someone’s trunk. In the evenings, Cathy makes

covert, late-night visits to Joni’s safe house in the belly of downtown Chicago.

After the stunning and rapid 90-minute “not-guilty” verdict, Joni escapes to Florida

with her kids and leaves a vaporous trail, never to be filled. While the fog of trauma

sticks to Cathy like black tar, she enters high school grappling with an untreated

nervous disorder, a fondness for her dad’s pills, and a shoplifting arrest. With newly

sprouted breasts, she foils sexual advances by Murph the Surf (a jewel thief in

Miami), her lesbian counselor, and her Robert Redford look-alike senior drama

teacher. In each case, she replicates the artful dodger. Cathy has learned well from

cheaters, sociopaths, and wife-beaters like Johnny.

In 1969, Cathy embarks on a fleeting, impactful romance with David, a brilliant

young writer. Both lover and mentor, David challenges her with one question:

“What are you going to do with the rest of your life?” She shrugs. “You’re very

smart. You have a great brain. You should get an education.” CUT TO:

SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY: Cathy earns stellar grades, trips on orange

sunshine, and swims naked in the local lakes. When the Symbionese Liberation

Army throws smoke bombs into her dormitory one night, she calls The Comic. “Dad

– I’m scared. Can you come get me?” He does.

On the five-hour drive, Dink tells Cathy that she has a secret sister, three years

younger. “I had an affair with a cocktail waitress in Kansas. I thought she was 18.

Your mom doesn’t know.” Cathy wants to jump from the speeding car, but the doors

are locked.

Back home and devastated, she cannot look at her mother. Within weeks, Cathy

lands a scholarship to UNLV. By this time, The Comic’s Wife has at last come to

adore and even bond with her daughter, however, it’s too late. Cathy must leave.

O’HARE AIRPORT, 1970: At the gate with Cathy, Dink suggests they take his old

flame to dinner when he visits Vegas. Cathy won’t have it. Summoning newfound

maturity, Cathy finally slaps him down. “No, Dad. You’ve been doing this to me my

whole life. I’m not your buddy. I’m your daughter. Normal fathers don’t tell their

daughters this stuff. I love you, but I’m done here.”

Without looking back, she boards the Pan Am jet for Las Vegas. The Comic stands at

the terminal window and watches her plane taxi down the runway as she embarks

on an entirely new life.