Prologue

“We were all broke and struggling.”

—Rudy Nöel, The Comic’s Agent

In the 1960s, a subculture existed right in the heart of downtown Chicago. It was the burgeoning nightclub scene—much of it run by the Mafia. Rush Street was a well-known haunt managed by Jimmy

Allegretti, a familiar crime syndicate name, while iconic clubs like the Chez Paree, Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Club, The Black Orchid, The Living Room, and the Sherman House booked famous and not-so- famous comedians—as well as sultry blond singers. Comedy was big in Chicago at that time, but it was different then. In the ’60s, comedy was much more elite, exclusive, and in the domain of grownups. There were no satellite comedy clubs that attracted youngsters. Seasoned comedians like Bob Newhart, Mort Sahl, Dick Shawn, Frank Gorshin, Shecky Greene, Shelley Berman, George Carlin, Max Cooper, and Sonny Mars were just some of the comics who headlined Chicago clubs and hotels.

The Chicago “locals” were a unique, close-knit (almost incestuous) tribe of performers. They reflected an era that no longer exists. These unknown entertainers traveled the United States, working in dingy dives, cheap clubs, and hotel ballrooms because they knew no

other life. My childhood was spent with those performers—hanging out in nightclubs, hotels, resorts, and even in our home, constantly inhaling secondhand cigarette smoke.

My father was a stand-up comic at the center of that Chicago universe. His name was Dink Freeman. He was never meant to be an insurance salesman, golf pro, business owner or rabbi. My father was meant to be a storyteller. He was happiest and most comfortable standing onstage, under a spotlight, holding a microphone. That was his pulpit. By solely telling hilarious, ethnic stories, The Comic fed us, clothed us, and paid the rent on a zillion cookie-cutter apartments during the course of my childhood. Calling himself “America’s Most Versatile Storyteller,” my father told jokes in every conceivable dialect while miraculously, never offending anyone—ever. It was a spectacular feat and he was brilliant. At the height of his career, which came later than most, he opened for Debbie Reynolds, Donald O’Connor, Sammy Davis, Jr., and The Harry James Orchestra, to name a few.

Growing up in this environment, I understood punch lines much better than fractions; I read Harold Robbins, dirty detective novels, and all the Playboys I could find. I also read Little House on the Prairie, but it wasn’t nearly as good as a column by Art Buchwald. Without question, I was much more comfortable in a smelly club than at an eighth- grade school dance. There were no neighborhood soccer moms at our kitchen table; more common were magicians, novelty acts, comics, adagio dancers, a famous chimpanzee named Chatter, sexy blonde singers, and one murderess. Rudy Noel, an ex–dancer–turned–agent, summed up the local climate and lifestyle accurately: “We were all broke and struggling.” And they were.

On work nights, my father, The Comic, changed into flashy suits and disappeared into the belly of downtown Chicago. On special occasions, I got to sit in the back of smoky clubs or hotel ballrooms and watch my father tell jokes. It was exhilarating. There was a huge payoff in doing this. After every set, I’d head straight to the women’s bath- room—not to pee, but to listen to the women talk about my father and his jokes. While these enviable adult females were busy applying lip- stick (something I wasn’t doing yet), I’d eavesdrop on rave comments:

“That comic was really funny.” “Who is that guy? I’ve never heard of him.”

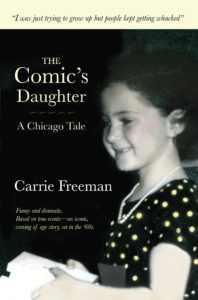

When the compliments hit a crescendo, I’d make a calculated approach. I learned at a young age that timing is everything. Disarm- ingly well rehearsed, I’d stick out my little hand with panache: “Hi, I’m The Comic’s Daughter.” (Note: I was really cute, in the true sense of the word. Not pretty or conventionally cute, but sort of awkward and adorable, with uncontrollable curly hair, freckles, and round cheeks.) In addition, my mother always managed to dress both my brother and me stylishly, so no matter how poor we were, we always looked good. Mom subscribed to the philosophy that it’s “better to look good than to feel good.” To this day, I look my hottest when I’m suicidal.

After I announced myself as The Comic’s Daughter, all the women fell in love with me. They inevitably cooed.

“Your father is so funny—so handsome!”

“Where ’d he get all those jokes and all those dialects?”

“He must be so much fun to live with.”

Every bathroom visit gave me a rush. I was special. I mattered.

Like yeast, I thrived on these encounters until I made my way to the next latrine. I appeared in every gin joint bathroom in Chicago, Miami, and the Catskills. Those powder rooms were key to my survival.

Via each public bathroom, I got my self-esteem and a (co-dependent) sense of self—just a few feet from a bunch of toilets.

My childhood went along like that until the fall of 1963, when Joni Morgan Mancuzzo, a beautiful blonde singer, murdered her husband, Johnny, three hours after I babysat for their two young children. Johnny Mancuzzo was my father’s theatrical agent, a member of the local Mafia, and a spectacular sociopath. At the age of thirteen, I suddenly went from having a crush on Paul McCartney to sharing my bed- room with a woman on trial for shooting her husband in his sleep. The thing is, I loved her dearly. This is how my adolescence began. When Joni shot Johnny, everything changed.